By Mattis Bulk

Almost everyone is familiar with the comics The Adventures of Tintin by the artist Georges Remi (1907–1983), better known as Hergé. In these stories, the reporter Tintin travels around the world with his dog Snowy from 1929 until Hergé’s death in 1983, experiencing all sorts of adventures. The Adventures of Tintin have been translated into 80 languages and dialects, making them second only to the Asterix comics in terms of translation into other languages. To date, more than 230 million copies have been sold, and new editions of the individual albums are still available in bookstores today.

Yet despite the consistently high sales figures of Hergé’s unique comics, there is a rarely discussed issue that casts the artist’s drawings in a different light. In The Adventures of Tintin, there are recurring indications of antisemitism, racism, and colonialism. But what exactly is problematic in these comics, and what does it mean for our time? How should we deal with antisemitism in popular works by an artist who is no longer alive? I would like to give a rough overview of these questions and offer a few points for reflection. Hergé’s work and the influences on and by him are, of course, far more extensive than can be presented here in a single blog post. This is therefore a strongly condensed and topic-focused presentation using the example of the comic artist Hergé.

In the course Religion and Society, we dealt with sociological approaches to the religious influences in society.

In the book An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, which we read in the course, Karl Marx’s theories were described as foundational and influential for contemporary sociology. One example discussed is how certain groups use religion to legitimize their own ideas and interests. Hergé’s comics can also be counted among these, as the beginning of his success story was strongly shaped by religious influences. When the artist received the offer in the 1920s to draw comics for the youth supplement of the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, the influential editor was the ultra-Catholic priest Norbert Wallez, who was not only a nationalist but also sympathized with fascism. He determined the goals of the new comic hero Tintin and his four-legged companion.

In class, we also discussed the relationship between media and religion. Both sides influence each other, as the sociologist Hodkinson formulated. He saw media not only as something that shapes society but also as a reflection of society. This observation can also be applied to Hergé’s Tintin comics, which in the early years were particularly shaped by the ultra-Catholic influences of the editor. This influence also promoted an extremely undifferentiated and sometimes incorrect portrayal of people from around the world whom the reporter meets on his travels.

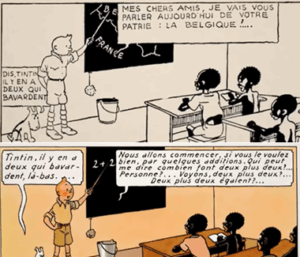

Thus, alongside antisemitism, the Catholic aversions to communism and capitalism can also be found in the early volumes. For example, in the third volume, Tintin travels to the Congo, which had long been controlled by the colonial power Belgium. As a result, there is both a positive portrayal of Belgian missionaries in the Congo and racist depictions of the Congolese inhabitants.

During the Second World War, Hergé was offered the opportunity to draw his comics for another weekly newspaper called Le Soir. In the adventure The Shooting Star, published from 1941 onwards, two men appear who, with their names and appearance reminiscent of National Socialist caricatures, reproduce Jewish stereotypes. The villain and antagonist in the story was also depicted by Hergé as an exaggeratedly Jewish person. The Jewish banker Blumenstein—whose name was changed to Bohlwinkel in 1954—supports an American expedition that is positioned in opposition to Europe. Whether this depiction can truly be called ideological, however, remains controversial.

Even though many more examples could be analyzed in detail, this small exemplary insight shows that the Tintin comics are shaped by the time in which they were created and the influences of Norbert Wallez’s ultra-Catholic worldview. At this point, however, it is also important to mention that Hergé revised some of his drawings for later album editions. For instance, a geography lesson given by Tintin in the Congo was later changed into a simple mathematics lesson. Throughout his career, Hergé made numerous such revisions.

Picture Reference: Hergé à l’ombre de Tintin, ARTE France, 82min., 2006

Additionally, in an interview regarding the discussed issues of racism and antisemitism, Hergé stated that he had only portrayed people in Africa the way Belgian colonialists had described them to him and that he had no other sources. The caricature of a Jew during the Second World War was, he admitted, unfortunately chosen but not intentional, as he knew little about the Shoah. When asked directly by the interviewer whether he saw himself as antisemitic or as an enemy of Black people, Hergé responded: “Of course not!” All of this, of course, does not excuse his portrayals, but it does show that Hergé was aware of problematic depictions in his works. The new editions available in bookstores today are all versions that were revised by Hergé himself.

Since these comics are still widely read today, I believe it would be useful to promote comprehensive, targeted research that examines in detail the background and motives as well as problematic depictions. There is already academic literature that, for example, deals with the Christian influence on Hergé’s comics or the stereotyped depiction of the Middle East.

Perhaps it is advisable not only to read the comics but also to engage with the background of the artist. This makes it easier to become aware of the context of their creation and the related problematic portrayals of people. Parents can also explain problematic depictions to their children before they read the comics and thus even contribute to a more open-minded worldview in their children. Publishers, too, can draw attention to issues and raise awareness with introductory texts—as has already been implemented in part.

I hope that, using Hergé’s The Adventures of Tintin, I was able to show that comics also shape society and that the worldviews conveyed in them deserve critical examination and should be questioned and reflected upon when reading today. Moreover, the comics themselves reflect society to some extent, particularly in Hergé’s early works through his ultra-Catholic environment.

In any case, I will look more closely when I read comics in the future.

How will you read comics now? Would you look into the background of the artists behind your favorite comics? Perhaps, with a bit of awareness of the issues, a combination of critical reading and the enjoyment of comic art is possible.

References:

- Handbuch des Antiseminitismus, Band 7, 2015

- Cora Alexa Døving: Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia: A Comparison of Imposed Group Identities, 2010

- Europäisch-Jüdische Studien Beiträge, Band 37, 2019

- An Introduction to the Sociology of Religion, 2024

- Tim und Struppi“ – Westliche Konstruktionen des Nahen Ostens in popkulturellen Medien, Eine Diskursanalyse zur Konstruktion des Anderen, 2024

- Tintin as a Catholic Comic, 2017

- Hergé à l’ombre de Tintin, ARTE France, 82min., 2006

- Interview Hergé: The Comics Journal 250, February 2003