A typical picture for Visual studies? One can say a lot in sociological terms about this. This is the type of pictures people usually ask us about.

Art history is an important part of Visual studies, and most of us who work in the field are art historians by profession. The somewhat problematic relationship between Art history and Visual studies is discussed in an open and inspiring manner in the collective volume Farewell to visual studies (2015), edited by James Elkins and composed of transcripts and responses from the 2011 Stone Art Theory seminar. The seminar brought together over 30 distinguished scholars who have made substantial contributions to Visual studies and related fields in different countries.

Some conclusions are quite clear from the discussions in the book: Visual studies is primarily a British and Anglo-American phenomenon, it has been dominated by social/sociological issues in connection to the Cultural Studies tradition, with much focus on content (or what an Art historian would call ”iconology”) and less on form and aesthetic/psychological aspects. The provocative title ”Farewell to visual studies” is probably intended by the organizer and editor James Elkins as a farewell to Visual studies as it has been, in its more limited aspects. Elkins would like Visual studies to become more ”difficult” (or complex, or interdisciplinary), less focused on contemporary Popular culture, and more open towards other types of images and longer historical perspectives. He asks why for example the scientific image has been largely neglected within Visual studies, and agrees with such scholars as Michael Ann Holly that Visual studies has increasingly lost contact with History prior to the age of Photography, Television and Internet.

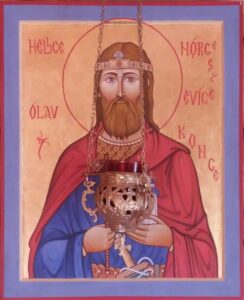

Few ask us about such pictures as this. This is also a political picture and very interesting for Visual studies. (”Holy Olav, eternal King of Norway”, newly painted Icon for the Orthodox chapel in Stiklestad).

Few of the contributors to Farewell to visual studies disagree with Elkins on these points. Some suggest explanations to why we have this situation. One quite natural explanation has to do with competition and the need in a new field to distance oneself from ”tradition”. Clearly Art history and History at large represents ”tradition” in this academic game. Still, practitioners of Visual studies are often Art historians or at least Arts people by training, and there is a reluctance towards studying pictures for which the usual methods and analytical tools in the Humanities are insufficient. Somewhat paradoxically, Visual studies seems to have become too unhistorical in terms of the choice of topics, yet too dependent on existing methods and theories in Art history. I think we’ve been trying to avoid these traps here in Åbo. It can be done by focusing more on methods and the development of alternative metods, rather than certain topics and periods. It is good to visit seminars at other departments and facultites (Philosophy, Psychology, History, Sociology, Biology…), and it is good to contribute to both Art history and Visual studies and teach both subjects in order to avoid narrow specialization. One excellent option to learn more about medieval culture and iconography (i.e., ”the study of pictorial content”) was the 2018 Iconographic Symposium in Trondheim/Stiklestad, Norway. There I found the newly painted icon of the Norwegian national saint Olav in the local orthodox chapel. In this picture the ancient rules and symbols of Icon painting are adapted to a contemporary national context in which the Orthodox communities only represent a tiny minory. More about the Iconographic symposium soon, I hope.