From now on I will start to write some blog enties in English in such cases where a topic might be of interest for other people than Swedishspeakers. We also have international students, for example at our Imagology course.

To associate our righteous hero Tintin with nazism might seem ridiculous at first, but there are some who would say that it is not entirely misplaced. Georges Rémi, who became known as Tintin’s creator under the name Hergé, used to be friends withn a certain Léon Degrelle. In 1929, they both worked for the same Catholic newpaper in Brussels. The first strips of Tintin were published there, and later in his book Tintin, mon copain, Degrelle claimed that he was the real model for Tintin. The journalist Degrelle became more and more personally involved with politics. He became the chief ideologist and leader of the Belgian equivalent to Nazism, Rexism. As a volunteer in Hitler’s army, he also earned decorations as a war-hero at the Eastern front, before withdrawing to Franco’s Spain where he remained until his death. As for Hergé himself, he basically shared the same convictions during the War, and only made his lip service to democracy when it was clear that Germany had lost.

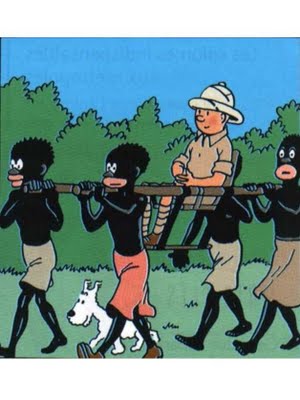

For a person living at that time and with such friends, it is hardly surprising that the Hergé of Tintin au Congo (1930) would render Africans in a highly stereotyped way. A couple of years ago, a major British bookshop chain decided to withdraw a new edition of Tintin au Congo from its children & youth’s section. The decision was made after a strongly formulated recommedation from the state Commission for Racial Equality. And yesterday, breaking news in Swedish media kicked off a flow of comments about the decision to remove all Tintin albums from display in the children’s area at the public Stockholm Kulturhuset (House of Culture). Behrang Miri, the newly appointed curator responsible for the decision, said to the daily Dagens Nyheter that visitors with African backgrounds had made complaints about racist pictures in Tintin, and that the removal was a part of a larger strategy to educate even small children to think critically about stereotypes in culture. He also said that introductory texts about the historical background for Hergé’s work (as seen in many new editions) are not enough.

Reactions immediately came. Probably the most articulate one is written by the daily Svenska Dagbladet’s new editor of culture, Martin Jönsson. In national Swedish Radio, Mr Miri was asked how there can ever be a discussion about these issues if people (and especially young people) are not even allowed to see the books. Mr Miri could’t really find any good answer to that question, and later the same morning (nb – the same morning that the news about his decision came!) he ”made a poodle” as Swedes say, i.e. admitted that he had gone too far. Still, today a scholar in comparative literature has written a comment in support of the Kulturhuset censorship. As for myself, I think that the ”house of culture” was now very close to become a grave of culture. One can write critically and expose the ideological patterns in the stories, like Dougal MacDonald of the Marxist-Leninist Party of Canada, but such criticism would die without the circulation of all kinds of messages and media in accordance with freedom of speech.

länkning pågår till intressant.se