An important statement of Visual Studies: From an exhibition by the artist Alfredo Jaar in 2013. Source: https://alfredojaar.net/projects/2013/

Hello! This is still the blog of the Visual Studies minor at Åbo Akademi University and I am still Fred Andersson, a Swedish art historian who has been running this business since it started in 2008. Recently I discussed the topic of blogs with some of my art history students – ”is there anyone who actually reads them anymore?”. Anyhow, we agreed that if you have a text-based blog, you probably write it mainly for your own sake, for testing ideas, using the blog as a ”sketch-pad” for more finished texts, probably also as a strategy to get rid of writing blocks. There are people who use Facebook and Instagram updates for similar reasons, sometimes posting full essays, but especially in the Smartphone mode the reading experience is not very pleasant. Let’s therefore continue with this Visual Studies blog. I guess I will still be the only one writing for it, and if you happen to be some people out there reading it, don’t hesitate to email me if you have questions or ideas (you’ll find my info in the ”Våra kurser/Our Courses” tab at this page). I had to disable the ”comments” function because of massive amounts of spam. All new entries will from now on be written in English, because over the years we have seen that to an increasing extent, exchange students are in majority among the participants of some of our courses.

A random example in Visual Studies: This image was ”made” a century ago in order to capture both the boys and the now demolished building in the background. The image ”tells us” about the situation of its making. Without text and archival information, it doesn’t tell much else. (Source: private.)

We have now, hopefully, left the COVID pandemic behind, and in the meantime the study structure at our faculty section KHF (Culture, History, Philosophy) at Åbo Akademi University has underwent some structural changes. It is, as yet, not very clear what consequences these may have for the future role of the Visual Studies subject. With continuous information work and ”marketing efforts”, for example the maintenance of this blog and the circulation of course information to mailing lists and in the Visual Studies Facebook group, I have been able to attract a sufficient number of students and to keep most of our courses running every year since 2008. However, due to other demanding tasks and the time-consuming adaptation to online teaching during the Pandemic, I have not been able to maintain these outreaching activities for the past two years, and the effects of this neglect are now clearly noticeable.

A small subject is always in a precarious position, especially at a small university with only one single individual (that is me) employed as full-time teacher and researcher of the subject. This single individual is probably even the only teacher in the whole of Finland: even though Visual Studies now exists at Tampere University also, the people there present the subject as a research network and don’t seem to offer any undergraduate courses (Tampere Visual Studies Lab, https://research.tuni.fi/visualstudieslab). Some other Finnish universities have courses in Visual Culture, which is not necessarily the same – I will soon explain why.

I have noticed that most students taking our courses are no longer aware of the existence of Visual Studies as a ”short minor” (in Swedish kort biämne) at our university, i.e. as a small program that you can choose as a parallel complement to your ”major” (in Swedish huvudämne). Some have found single courses that have been recommended as optional in other subjects or study units (in Swedish kurshelheter), others are probably interested in only certain specific aspects of Visual Studies (such as film studies), and many exchange students have realized that some of our courses are among the few in the humanities that are given in English. All this is well and good, but it is obviously time for a reminder that Visual Studies exists as a separate discipline at universities worldwide, and that there are certain reasons for its existence. These reasons are also the reasons why our courses look they way they do, and why they should preferably be taken in a certain order if you want to choose Visual Studies as your minor subject. (See the ”Våra kurser/Our Courses” tab.)

Visual Studies has an obvious connection to Art History – a much older subject that has been taught at European universities for at least 200 years. Most scholars who regard themselves as belonging to Visual Studies have a formal education as art historians, and most research groups or departments with ”Visual Studies” in their official names have been sub-sections or ”outgrowths” of departments of Art History. Because of its organizational connection to Art History, Visual Studies is typically regarded as the study of human visual culture – or more specifically as Visual Culture Studies. The difference with Art History is simply the word ”art” – Visual Culture is not limited to what we usually refer to as ”art” (for example objects exhibited at ”art galleries” or collected at ”art museums”). The history of visual culture is the history of how humankind has shaped its visual environment and developed means of visual symbolism and communication. When limited to Visual Culture Studies, research in Visual Studies normally focuses on aspects of human behavior that are dependent on culturally determined conventions and codes, the dominant research paradigm being that of cultural constructivism.

When taken to extremes, cultural constructivism tends to result in a rather limited worldview, according to which almost everything in life could be explained as dependent on language, culture and learned behavior. One case in point is the famous Sapir-Whorf hypothesis in linguistics, which states that our perception and our understanding of the world around us is shaped or ”moulded” by the terms and concepts available in our language, and not the other way around. In its strong version, which is today abandoned by most linguists, this hypothesis would potentially lead to such resasonings as this one: Let’s assume that a language has only three basic color terms, and that these are black, white and red. Then, its speakers would not be able to perceive other colors.

How are we to test if this conclusion is true? Indeed, there are still people who in their childhood only spoke a language with no other basic color terms than those mentioned – for exemple some languages spoken by indigenous groups in Australia. Today, they most probably speak English too. If, in their childhood, they were subjected to various psychological tests designed in order to determine whether they could see or not see what ”we” Westerners see, such tests would still beg the question of what it means to ”see” and to perceive. Do we have, ourselves, names for all chromatic nuances we can distinguish? Hardly so: we would then need thousands and thousands of colour terms, and be able to remember them and distinguish between them. There is no room in our verbal memory for such massive amounts of fine linguistic distinctions that only refer to color. The visual ability of distinguishing colour is evidently not dependent on the number of color terms in language. Paintings and other visual artifacts produced in cultures with limited color terminology is by no means less colorful and nuanced than in other cultures, and most probably a more developed terminology has never been needed for social interaction in the group. Similarly, the term brun in old French covered a range of nuances from brown to dark violet – there was not yet any need to attach those nuances to separate word labels.

Research in perception repeatedly demonstrates that seeing is both a biological mechanism and a social activity. When someone or something draws our attention to a detail in our environment we ”attend” to that detail and tend to neglect the rest. This is shown in a well known experiment, in which people watching a ballgame don’t notice the actor in a gorilla suit entering the scene, because they are busy counting the number of times the ball is passed (Watch here, https://youtu.be/vJG698U2Mvo). Thus, vision partly works in a ”top-down” fashion, as psychologists use to say, because we constantly move our eyes and activeley seach out what we want to see or what we expect to see.

But vision also works in the opposite, ”bottom-up” direction. Raw visual data is received by the photoreceptors in our eyes (or, more correctly, in the retinas of our eyes), and is processed for the extraction of only those features and contrasts that are necessay for perception. Vision is selective and active. The supposition that we would not ”see” things if we cannot ”name” them rests on a limited understanding of the relationship between sensation and meaning, or between raw perception and developed cognition.

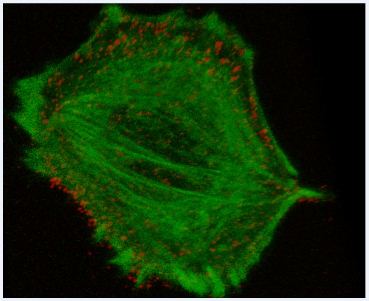

Neuro-electrical excitation levels of responsive fields (with ON and OFF regions) when registering different points around a light/dark border. Responsive fields only partly overlapping the borders have the highest response levels (above and below zero level), resulting in the perception of a sharp contour. (Source: Thompson, Trosciano & Snowden, Basic Vision)

Actually, ”meaning”, in a wider sense than only ”verbally expressed meaning”, is generated already at the ”primitive” level of extraction of contours by the photoreceptors. As anyone who has ever tried to draw a picture of an object would know, there are no contours ”on” the object. There are only surfaces. Producing a drawing with contours is a process akin to how the organisation of photoreceptors in networks of ”responsive fields” is optimized for the registration of changes in light intensities in a perceived scene: the borders between lighter and darker regions are decoded as contours, from which higher functions in the brain can ”conclude” what kind of object or shape we are perceiving. After some 100 years of advanced neurological science we still know very little about how this actually works. Scientists surely know how visual features, such as size, placement, orientation, colour and movement are processed by specialized regions in the brain, and that these regions are all interconnected in a neural network of amazing complexity, but there is still no clear answer to how all these features and pieces of information are coordinated and understood as something we can point to and refer to with a term in language, for example ”a ball”, ”a cube” or ”a house”.

It seems that the more we study these matters, the less we know, and the more we will refrain from simplified generalizations such as ”there is nothing outside of language!” or ”everything is biology!” Sometimes, Visual Studies can provide space for sharing and comparing contributions from different disciplines: what do historians, sociologists, linguists, computer scentists, biologists have to say about the use of visual skills in their work, and how can their own research contribute to our knowledge about the visual? To the extent that this sharing and cooperation is not limited to the humanities, Visual Studies could then be defined as a more open and inclusive field than Visual Culture Studies, or as Visual Culture Studies without ”culturalist” bias. The same is true of the developments in interdisciplinary language studies, often involving pictures and ”visual thinking” also, that are known as cognitive linguistics and cognitive semiotics.