This is a little report on what we have been doing the past weeks in the Visual studies program. We now start every academic year in English, and with perception. As the title of our course book Basic Vision says, the perception course is really about the very basics of vision and brain. ”Why do you need vision science in visual studies?” some people ask, believing that visual studies is not a scientific field.

They are partly right, if we use the word ”science” in its more limited sense, meaning hard and objective science. Visual studies is a continuation of programs in Cultural Studies and ”Visual Culture Studies”, beginning in Britain in the Sixties as a part of sociology and cultural history – disciplines that some proponents of hard science would associate with witchcraft rather than science. Some people have grown tired of the one-sided ”culturalism” of these circles and proposed that Visual studies should learn less from Cultural studies and more from for example Medicine and Computer Systems.

There is a growing awareness that our conceptions of Nature and the Universe are now increasingly based on scientific images that are very different from those we know from earlier times. These images are visualizations of highly complex sets of data, and it is not possible to understand the principles and processes behind them if you don’t have access to some specialized knowledge. Thus, the divide between the ”two cultures” at universities (i.e. the scientific and the humanistic) tends to widen even more. If populated with open-minded people with a broad range of knowledge, Visual studies might help the two cultures talk again.

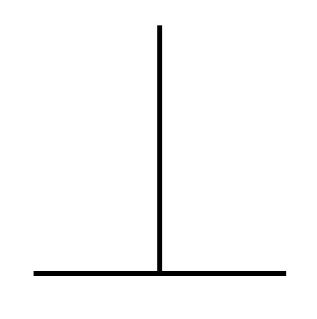

A very basic phenomenon of basic vision. The two lines are exactly the same length. Why don't they look like they were? (In fact, vision science is still struggling with this question.)

The first priority would be that we learn to talk about our own field of study – images and vision – in a scientific way, if only on a very basic level. This is what we do in the course Image Perception and Cognition. Our participants represent a wide range of interests and fields – some are from the humanistic field, some study computer science, and some are in the master’s program of the Bioimaging group in Turku. These bioimaging students will soon work independently with scientific imaging. Maybe they will end up in a research group studying the brain, and then contribute to bringing new knowledge to the field of vision science! Image Perception and Cognition is our most popular and successful course this far – mainly, I think, because it is basic and inter-disciplinary.

Being essentially ”culturalists”, me and my colleagues here at the faculty of arts must of course adopt a quite humble attitude in these contexts. How lucky we are that we have an experienced vision scientist and brilliant teacher to handle this course – Tarja Peromaa of the Visual Science Group at Helsinki University! Under her guidance, we have now read the first four chapters of Basic Vision and started to orient ourselves at ”the first steps of vision”. We are starting to understand that vision is both dynamic and selective, and we are beginning to remember the names of the different pathways, regions and cells involved in the visual system. It is like learning to talk a language. Before you know the basic terms and structures in a language, it is impossible to form sentences or to understand them. Soon, we will all know the meaning of terms such as ”cornea”, ”fovea”, ”retina”, ”ganglion cell” and ”lateral geniculate nucleus”, and understand a bit of what vision scientists are talking about when they are describing perceptual processes that art critics have been talking about all the time, but in a much more intuitive and everyday manner.

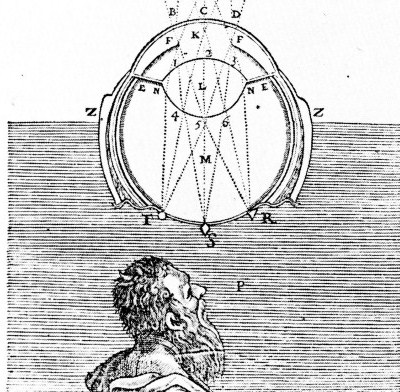

Vision science is not a new thing – in Europe it has been going on at least since Leonardo da Vinci tried to figure out a way to inspect the ”picture” projected inside an eye from a dead cow, hoping to see the world in the same way as a cow does. This idea was based on the same kind of misunderstanding as the diagram by Descartes that I show details of here. What misunderstanding? Well, the misunderstanding that Consciousness (of a cow or a human) is like a small person sitting somewhere inside our heads, looking at the pictures of our retinas (the ”screen” at the back wall of our eyes) like someone visiting a movie theater. The philosopher Antony Fredriksson will discuss the history of this idea in our course about moving images. Modern brain research gives ample proof that visual perception or any perception doesn’t work like that at all. In fact, there is no picture to be seen on some inner movie screen, but only a myriad of light-sensitive cells – the so called photo-receptors of the retina – each picking up a certain wavelength and intensity of light from a certain point in the environment, then sending it upwards through the numerous crossroads of the visual pathway. Somewhere – but definitely not in one place only – all these isolated signals are finally ”computed” together to form a part of our current field of consciousness. In this way, the digital camera with its receptive screen of isolated sensors is a better metaphor for vision than the traditional analogue camera.

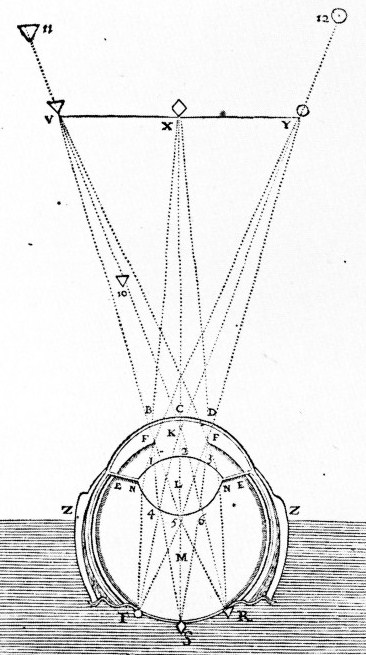

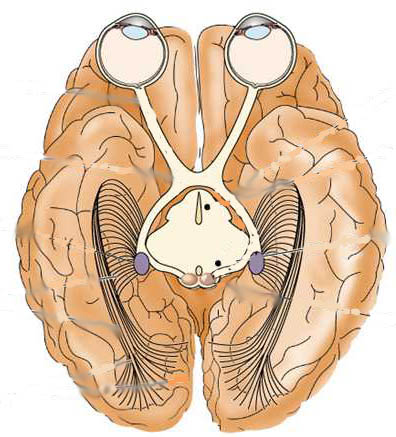

Modern picture of the basic visual pathway. The blue patches at the center are the LGNs (Lateral Geniculate Nucleae)

Most people know that we have two kinds of photo-receptors in the retina – rods and cones, rods being responsible for night-time vision and cones for color perception. What happens further along the road is less common knowledge. All the different signals from the photo-receptors are ”cabled” through the two optical nerves that meet at the first crossroad – called the ”optical kiasm”. That is what you see in upper half of this picture. Then the signals from the left side of the field of vision (of both eyes) are cabled to the right side of the brain, and vice versa. This happens in the ”cables” known as the visual tracts. The signals arrive at the small nucleae with the difficult name – the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus, or LGN. They are located deep inside the brain, within each side of the central region called Thalamus. The LGNs consist of at least two types of cellular layers, responsible for transmitting different kinds of information to different parts of the cortex (the cortex is the outer, ”wrinkled” parts of the brain). In this way, high-contrast information and most color information is sent through the parvo-cellular layers, while low-contrast information about movements is sent through the magno-cellular layers. It is believed that some problems with reading and writing could be due to deficiencies of the magno-cellular system.

In the lower half of the picture above, it is shown how numerous axons forward most information to the main visual center of the cortex, which is located at the very back of your head, in the region that we call the occipital lobe. And this is where we were in the course this week, learning how different cells at this ”station nr 1” (or V1) of the visual cortex are responsible for decoding specific kinds of information, for example the orientation and position of edges.

Probably our students are already busily reading the chapters for next week’s lecture, dealing with depth perception, color perception, and movement. Then, we will learn more about other visual cortex regions apart from V1 – Vision science discovers new regions all the time! Of special importance are V4 and V8 (centers for color perception) and V5 (movement perception). Look at this cover from the 2006 edition of Basic Vision. It is a popular perceptual illusion that was created by the Japanese artist and researcher Akiyoshi Kitaoka. It is basically a pattern of striped circles-within-circles, but the illusion that they are moving and the addition av small red tongues makes it easy to interpret them as snakes. Why do they seem to move? It is actually because of the division of different signals at LGN and the fact that green-black and blue-white contrast is higher than blue-black or green-white contrast. Still unclear? The exact answer is in Chapter six in Basic Vision, and in the next post on this blog.

Länkning pågår till intressant.se