This week, when social and sociological aspects are discussed in our course about comics (also see previous post), we give you this update by Fred Andersson:

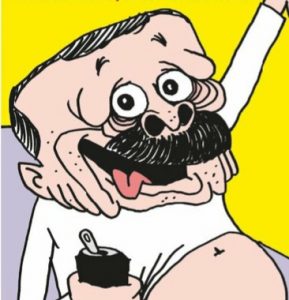

Again ordinary French citizens are assassinated outside their workplaces for no other reasons than having shown the ”wrong” kind of images to the ”wrong” kind of people, or simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Again terror alert levels are raised all over Europe. Meanwhile, the famous French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo shows no fear; its cartoonists continue to ridicule the rich and the powerful in a manner which is essentially a French democratic tradition since 1789. Recently, a cartoon of AKP leader and Turkish president R.T. Erdoğan as the generic male working-class TV-watcher in underwear, lifting the abaya/robe of his giggling, veiled and tray-carrying ”wife”, exposing her ”lower back”, adorned the front page of Charlie Hebdo. Speech bubble: ”Ouuuh! Le prophète!” (Oh! The prophet!). Headline: ”Erdogan. Dans le privé, il est très drôle” (in private, he is very funny).

Note that for attentive readers of the magazine, this is Erdoğan depicted in the same attitude and position as the stereotype of a racist and hypocritical French male, of an earlier Charlie Hebdo frontpage, no 1207, 9 September 2015.

The diplomatic consequences were imminent. In Turkey ruled by Erdoğan, an insult against the president is today treated by Turkish legal and executive offices as an insult against all of Turkey. According to this logic, all of France is held responsible for one single provocative cartoon, and the statements by Émmanuel Macron in defence of the freedom of speech is seen as a confirmation of a state-sanctioned aggression against Turkey, not as a defense of a general democratic principle strongly associated with the constitution of the current (fifth) French republic and the first amendment (1791) of the United States of America.

Why don’t I reproduce here the whole front page of Charlie Hebdo? Simply because I do not dare. Finland occupies a middle position between those countries which currently have no legal restrictions against blasphemy (such as France, Sweden and the USA), and those in which blasphemy can be a reason for imprisonment (e.g. Russia, see the Pussy Riot case) or even death sentences (Iran, Saudi Arabia).

The Finnish legal code, paragraph 10 in Chapter 17, defines it as a ”Crime against the protection of faith” if a person ”Publicly expresses blasphemy against God, or with an abusive intention defames or defiles something which is otherwise regarded as holy by a church or a community implied by the law of the freedom of religion”. Certainly the muslim communities are among those implied by the law which this paragraph refers to, and it is not wholly impossible that a lawsuit could be initiated by certain groups against newspapers and institutions in Finland who choose to publish or show the Erdoğan cartoon. Remember that Erdoğan is represented as exclaiming: ”Le prophète!”. The presence of the holy notion of the Prophet in the context of alcohole (beer can and wine glasses) is certainly enough to produce outrage among many believers. Even worse is the connection between the holy Notion and the exposed female parts, i.e. the essential ”butt” of the joke.

Even in countries without explicit laws against blasphemy, such as Sweden, cartoonists and editors have to consider their choices with great care. The case of the Swedish artist Lars Vilks exemplifies the consequences that can follow, for both the individual and for society, from acts of intentional provocation. Thirteen years after Vilks’s drawing of Muhammed as a ”roundabout dog” (a very Swedish notion) was first shown, and ten years after that drawing became the stated reason of attempted terrorist attacks i Stockholm (on December 11 2010), the artist still ”enjoys” 24-hour police protection and a very restricted life.

Apart from the risk of becoming a victim of religious extemism, there are other risks as well for publishers and public individuals who show support for such artists as Vilks and the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. You will probably be seen as a defender of certain racist and sexist stereotypes often used in satire, and your name will be associated with political sentiments alien to most representatives of western Academia. In the political left of consensus-based northern countries (but also in the USA), such individuals as Lars Vilks and Aron Flam (see next post) have come to be regarded as belonging to the far right, as they do not confirm to certain standards seen as necessary for a civilised debate. To a great extent, they have come to be seen as friends of the enemy (e.g. friends of radical Sionism) and then by association as enemies.

It is noteworthy that the only major media channel in Sweden which has published the Erdoğan cartoon is Expressen, the major liberal evening paper of the country, published in Stockholm. Expressen also published a lengthy comment on the case by Lars Vilks (unfortunately behind subscription wall).

As an editor of any paper or publication, the choice whether or not to publish controversial or ”politically incorrect” content will put you to an ethical test. This test can be described in the philosophical terms of general ethics: will you act according to consequentialism or according to deontology? (In Finland, Maaret Jaakola has studied Finnish cultural journalism with regard of this aspect, among others). If you act in the manner of a consequentialist, you will consider and evaluate all possible consequences of your action. Probably the negative consequences will seem to far outweigh the positive ones? Probably you will ruin a person’s life and career because of accusations or criticisms that you are about to publish? Probably you will become associated with political circles to which you certainly do not want to belong? Probably you realize that your friends will turn their backs on you? Then you will probably not publish.

If you are, on the other hand, an editor who adheres to the other and deontological extreme of media ethics, the consequences which may follow from your act really has no bearing on your decision. If a choice is deontological, it is only based on your inner conviction of what is necessary and morally right. You will probably refer to the principle of the freedom of speech, and to the duty (indeed the moral duty) of the press and the media to reflect in an unbiased manner all explosive facts and all political standpoints and interpretations, no matter how scandalous and how different from your own personal views.

In the French media climate, such channels and publications as Charlie Hebdo can pursue a secular satire in a manner often strongly reminiscent of earlier anti-semitic stereotypes (known in both leftwing and rightwing varieties!) and receive unanimous support from the president of the Republic as a part of his new campaign against fundamentalism and un-republican values (with support from the majority of the French left!) This media climate is essentually based on deontological approaches to media ethics. It is a climate which is impossible in Sweden or Finland. Here, those who refuse to acknowledge any restrictions of expressions and opinions in public discourse often refer to themselves as fundamentalists of a rather peculiar and liberal kind: as first amendment fundamentalists (in Swedish yttrandefrihetsfundamentalism).

This year in Sweden, the legal case against the satirist and self-styled Jewish conservative Aron Flam has shown the consequences that would follow if copyright laws were applied in order to restrict the right to paraphrase and parody images. The recent death of the communist author and activist Jan Myrdal has given occasion to some heated debates on his intellectual legacy: Myrdal’s life and work exemplifies how a very consistent application of ”first amendment fundamentalism” in combination with anti-imperialist political standpoints can result in difficult paradoxes. I will return to both Flam and Myrdal in the next post.

Pinged at bloggportalen.se