Åbo Akademi doing some ”visual sociology” in Bogotá, Colombia, September 2023. (Photo L. Conde-Aldana)

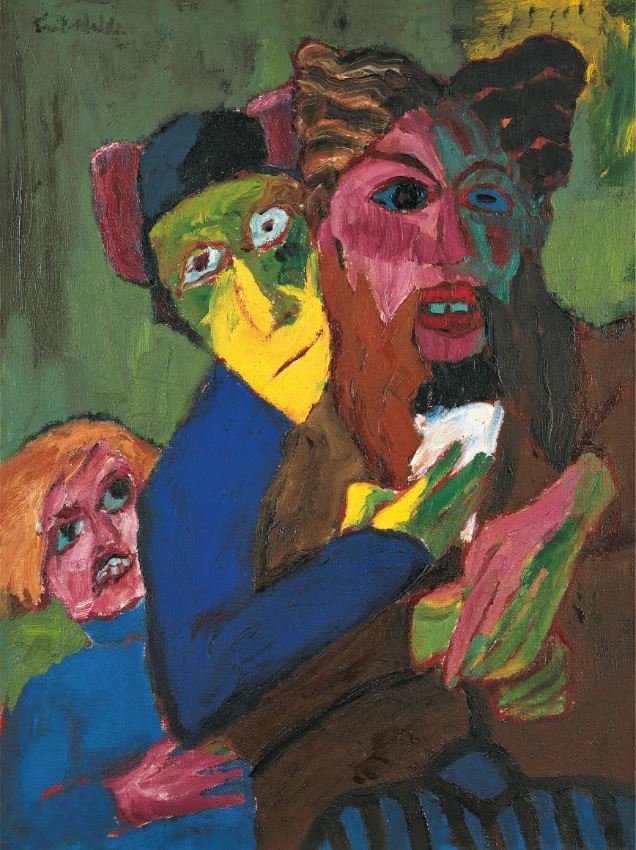

Update: In 2024 sixteen years have passed (2008-2024) since Visual Studies started as a minor undergraduate program at the then Department of Art History (Konstvetenskapliga institutionen) at Åbo Akademi. Today both Art History and Visual Studies are part of the section KHF (Culture, History, Philosophy) at the FHPT (Faculty of Humanities, Psychology and Theology). In Visual Studies we are now developing a closer connection to historical and anthropological aspects of the visual: next spring the course Visual Sociology and Anthropology (5 ECTS) will for the first time be given in English for both Åbo Akademi students and exchange students. The associate professor of Visual Studies also supervises Master and Doctoral theses in art history, and participates in the research seminar for Cognitive Semiotics at Lund University in Sweden. He is also a member of the editorial board of the online academic journal ICO: Nordic Iconographic Review, located at Lund University, and participates in an international project for re-launching Visio, the journal for Visual Semiotics (originally published in Canada). Both Visual Semiotics and the study of Iconography have been important parts of Visual Studies ever since the international beginnings of anglophone Visual Culture Studies and German ”image studies” (Bildwissenschaft) ca 40 years ago.

With the aid of guest teachers from Lund University, the University of Turku (UTU), and the Visual Neuroscience group at Helsinki University, we have offered two basic courses in Visual Perception and Behavioural science during 2014-2019: Visual Perception and Cognition (5 ECTS) and Eye-Tracking Methodology in Visual Studies (5 ECTS). Due to a number of factors, some caused by restrictions during the Pandemic 2020-2022, we had to discontinue Eye-Tracking Methodology in 2020 and Visual Perception and Cognition in 2022. During the same period, structural changes of the KHF study program meant that the course Från avantgarde till global konst (”From avant-garde to global art”), on the history of 20th Century visual art, was no longer included in the basic level studies in Art History. It was then decided to continue the course, but to include it as optional in the Visual Studies minor instead. It is given in Swedish as a fully on-line course with pre-recorded lectures.

Our 5 ECTS course in Visual Rhetoric, given in Swedish as Visuell retorik: Propaganda och marknadsföring (”Visual Rhetoric: Propaganda and Marketing”) has met a similar fate — it is now fully online with pre-recorded lectures from the Pandemic period. As the study of Visual Rhetoric is a rapidly expanding field (with a close connection to Cogntive Semiotics), these lectures will soon be outdated and we will have to develop the course further. Participants of the course have contributed to research in Visual studies by collecting and coding a large number of commercial videos from the Internet (mostly Youtube) between 2016 and 2019: the outcomes of this exercise is part of an evaluation of criteria for identifying instances of visual rhetoric in commercial messages, recently published in the academic journal Cognitive Semiotics (Mouton De Gruyter, Berlin).

During the Pandemic, we were recommended to develop the sociological and anthropological aspects of Visual Studies more and to bring the course schedule into closer correspondence with the international Master programs of our Faculty. Consequently, a considerable amount of time was dedicated last Spring to the development of our Visual Sociology and Anthropology course. It was adapted from Swedish to English and given as a first ”test-run” with a small group of Swedish-speaking students. The trend is that more and more of our courses are now given in English for all categories of students. A course in basic semiotics that we gave (with some modifications) in Swedish between 2009 and 2024 has now changed both name and language: starting in January 2025, it will henceforth be given as Visual Semiotics and Storytelling (5 ECTS). Rather than focusing more narrowly on one particular method or theory of Visual Semiotics (for example Structuralist analysis), we will now provide more of an overview of how different theories and approaches have contributed to the study of how images are actually processed and understood by people, and how perceptual and cultural factors interact in this process. Each week, analytic exercises in visual image analysis will support the learning and the application of the theories.

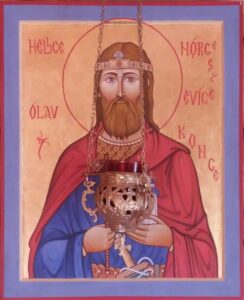

Biovisualization: neural axons of the human brain. Image source: Tamara V. Tulaikova and Svetlana R. Amirova, ResearchGate.

Most of our courses are now concentrated to the Winter and Spring periods, with only two exceptions: the aforementioned online Art History course and our international course on photography and cinema: Photography and the Moving Image (5 ECTS, November to January). These somewhat skewed proportions are again due to structural and organizational changes at our Faculty. One of the optional courses still has a strong connection to the behavioral sciences: it has been offered successfully for ten years and is called Visuality and Visualization of Information. Many participants in the course have been from the Master program of biomedical visualization (BIMA), but students from the Social Science and Humanities faculties have also participated and have reviewed the course favourably. Unfortunately, we no longer have a basic course in visual perception and neurology that can prepare students for the more scientific aspects of image perception and visualization, but we usually recommend that one should familiarize oneself with some basic literature (such as Basic Vision by Snowden et al.) before joining.

For Swedish-speaking students who want to include Visual Studies as a minor in the Bachelor programs of Culture (KHF) and Language studies, we still offer the course Visuell analys as a course based on hands-on analytical exercises. This has been an effective and popular approch ever since the course started in 2008. For the more historically or aesthetically inclined, we also offer our international Comics course, Comics – Interdisciplinary and Cultural Perspectives, which will henceforth be given in April and May. At the start page Våra kurser / Our courses at this blog, all the course descriptions have been updated this Autumn, and there are links for those students who want to access the Åbo Akademi Moodle and take a more detailed look at the courses right away (no registration keys are needed). Likewise, the links to various Internet resources and to other universities with programs in Visual Studies, to be found in the right-hand directory of this page, have been updated very recently.

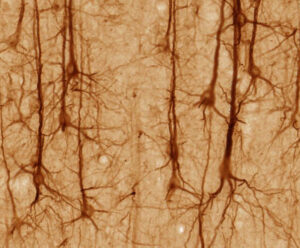

Sixten Ringbom, professor of art history at Åbo Akademi 1971-1992. Photo: Åbo Akademi image archives.

Some research activities of Visual Studies at Åbo Akademi between 2019 and 2024: There has been no time to start bigger joint projects or apply for funding, but invitations to contribute to journals and research anthologies have been answered. We participated on behalf of the section of Art History at Åbo Akademi in the seminar Hundra år av svensk konsthistoria – och sen? (”Hundred years of Swedish Art History – and then?”) at Uppsala University in June 2019: see program in Swedish as pdf. One of our talks at the seminar was then developed into the book chapter ”Is Finland Swedish? The role of the Swedish language, Swedishness, and Swedish history in Finnish art historiography” during 2019 and 2020. After an additional 2-year editing process, the chapter was published in the research anthology Swedish art historiography —institutionalization, identity, and practice from Nordic Academic Press in 2022: The whole anthology is available as pdf here (Lund University Library portal). During collecting and reading a considerable amount of Finnish and Finland-Swedish research in art history from the 100 year period 1920-2020, we also had occasion to look more into the work of our former Åbo Akademi art history professors: Lars Ivar Ringbom (1901-1971) and Sixten Ringbom (1935-1992). Our Archive of Art History (Konstvetenskapliga arkivet, link) is currently in the process of exploring and cataloguing additional documents related to the research of the two Ringboms. On the occasion of the re-publication of Sixten Ringbom’s book The Sounding Cosmos in 2022, an article on Ringbom was published in the Åbo Akademi science journal Meddelanden (in Swedish). Some of Sixten Ringbom’s later studies of pictures and narrative have an obvious interest for Visual Semiotics and narratology.

”Mayday Demonstration”, painting by Johan Ahlbäck (1895-1973) in the collections of the Dalarnas Museum, Sweden.

Much research time in Visual Studies during the Pandemic year of 2020 was spent collecting material for two extensive research articles covering the iconography and visual rhetoric of political propaganda: Iconography of the Labour Movement 1 and Iconography of the Labour Movement 2. As it turned out, these two articles appears to have been one of the most read from our Faculty at Research Gate during 2021-2024. The Labour and Worker’s Movement theme has been continued in collaboration with labour movement organizations in Sweden and colleagues at Malmö University. At invitation from the Johan Ahlbäck Association (Ahlbäcksällskapet), research was conducted between 2021 and 2023 for the main chapter of the book Inte vackert men omutligt sant: Johan Ahlbäck, arbetarkonstnären från Smedjebacken (”Not beautiful but immutably true: Johan Ahlbäck, the working class artist from Smedjebacken”), published in 2023. As image editor, our associate professor was also responsible for the documentation of Johan Ahlbäck’s artistic oeuvre and the selection of illustrations for this art book. Following discussions with Magnus Nilsson, professor of comparative literature at Malmö University, and a conference on Nordic Comics in Malmö in October 2021, we have also put together an article on the phenomenon of Working Class Comics for an anthology that will be published in April 2025 by Malmö University and the academic publisher De Gruyter (Berlin / New York).

From the start, the ambition of Visual Studies at Åbo Akademi has been to specialize and focus on Semiotics. There has always been a connection to Lund University and the Centre for Cognitive Semiotics (CCS, 2009-2014, now the Section for Cognitive Semiotics) that was established there by the late professor Göran Sonesson (1951-2023). There has therefore been a need to make our small writing- and documentation projects here in Åbo/Turku relevant also for semiotics. In some cases this has not been possible, because the aim has been merely historiographic (see for example the ”Nordic Art Criticism” section of this blog), but both the work on Labour movement iconography and that on Working Class Comics contain some elements of what is often referred to as Socio-Semiotics. With the aim of starting a methodological discussion regarding possible points of correspondence between Iconology/Iconography (as a speciality of Art History) and Semiotics, the one-day doctoral seminar Exploring the Boundaries of Iconography was arranged in November 2021 in collaboration with Art History (konstvetenskap/taidehistoria) at Åbo Akademi and UTU. A speech from the seminar has been published in English in ICO (Nordic Review of Iconography) no 3-4 2022 (Liepe), and a response is forthcoming in ICO no 1-2 2024 (Andersson).

Typical situation during the Pandemic: academics trying to get Zoom in order. Vilnius November 2021: Paulius Jevsejevas, Karl Joosep Pihel, Fred Andersson.

While Iconology/Iconography is mostly associated with the methodology of Erwin Panofsky (1892-1968), we wish to also stress the importance of another scholar of Jewish European descent but active in America: Meyer Schapiro (1904-1996). Schapiro was clearly a pioneer of both the Modern study of Medieval Iconology and of Visual Semiotics as applied to various periods in cultural history: thus his research is an obvious point of departure if we want to study connections between the fields. A paper on the topic was presented by Visual Studies at the 12th conference of the Nordic Association of Semiotic Studies (NASS) at Vilnius University, Lithuania, in November 2021. All sessions were recorded by NASS and the session chaired by us can be watched here:

NASS XII Session 5: Karl Joosep Pihel, Fred Andersson, Evripides Zantides (Youtube)

A much expanded version of the paper, comparing different approaches in Visual Semiotics (Structuralist, Cognitive, Social) and relating them to the pioneering work of Schapiro, was published in Volume 18 (2023) of the journal of the A. J. Greimas Centre for Semiotic Research in Vilnius, Semiotika:

In connection with our courses in Semiotics and Visual Rhetoric, and exchanging texts and ideas with Semiotic research centers in Belgium and Brazil, we have also made efforts to present francophone research to students and colleagues who do not read French. Especially the work of the Belgian research collective known as Groupe µ has has been a source of productive reflection and methodological application. Articles presenting the theories of Groupe µ have been published as outcomes of our research in Visual Studies in 2010 (Nouveaux Actes Sémiotiques, English), 2015 (Estudos Semióticos , Portuguese) and 2016 (Taidehistoria Tieteenä, Swedish). A further article in English with a presentation of the main elements of Groupe µ’s contributions to literary and visual analysis, and the implications of such analyses for a general ”theory of meaning” in Cognitive Semiotics, was published in 2023 in Volume 3 of the book series Open Semiotics, edited by Amir Biglari (Université de Limoges) for the French publisher L’Harmattan:

The digitalisation of the journal Visio (1996-2005), journal of the International Association of Visual Semiotics (AISV-IASS), is a cooperation between members of AISV-IASS from Åbo Akademi, the University College of Kristianstad (Sweden), the University of Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, and the University of Lyon. Visio is a journal that has been difficult to order and access. The digitalisation of all issues will now make avaliable a large corpus of texts, mainly in French but also in English and Spanish, covering a wide variety of topics, methodologies and national cultures during a dynamic and inspiring period of the development of Visual Semiotics as a specialized field of research. It can be assumed that many of these texts, and the topics and projects they describe, are still unknown to the majority of researchers active in the field — especially those of the anglophone world. When published online at the OJS online journal platform of Lund University, the Visio archive will give the academic community and the general public a much improved access to sources that throw light on the history of Visual Semiotics and the relationship between its different ”schools” in France, Belgium, Scandinavia, Canada and Latin America.

The Visio digitalization project, and plans for the future of the journal, were presented in a session of the 13th congress of AISV-IASS in Bogotá (Colombia). The conference was held at the Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano from 28 September to 1 October 2023. When we presented the project, we did it more as a discussion with other conference participants than as a conventional presentation, and in addition to representatives from Åbo Akademi (Andersson) and Paris 8 (Reyes) some members of the original editorial board and scientific committee of Visio were also present. Notably, professor Jacques Fontanille from Université de Limoges, member of the editorial board from the start in 1996, gave a well prepared speech on the history and future of the journal. An inspiring congress, the AISV-IASS 13 in Bogotá also gave rich opportunities for exploring the life of the city and its many museums (see picture at the beginning of this post).

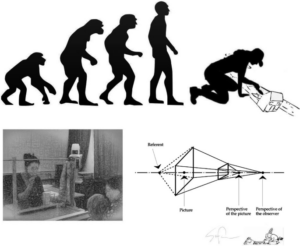

”Visual abstract” of the last article published Göran Sonesson, 2023: Humankind from Ape to Archaeologist; a psychological experient with children; the geometry of visual perspective; Sonesson’s signature; the Rabbit Scribe of the Mayans (compare next picture). Source ResearchGate.

To be a semiotician in the Humanities often implies a contradiction of aims and interests. In the Humanities there is a tendency to specialize rather narrowly in the study of specific periods, places, and even single individuals, such as a certain artist or a certain writer. By contrast, semiotics is more general in its aims. As the late Göran Sonesson used to put it, semiotics is ”nomothetic” (about developing and testing models) and not ”idiographic” (which literary means ”recording the individual”). Cognitive Semiotics focuses on larger developmental patterns: both in child development and in the evolution of Humankind at large. This is also true of the Cognitive Semiotics centre at Lund University. Both linguists, developmental psychologists, primatologists and some art historians have contributed to the projects there. Looking back at the work of art historians who were active at the turn of the century 1900 one will discover, however, that they were often far more ”nomothetic” than people of today may expect. Some of them worked at the level of global world history and constructed general theories about cultural development and human creativity – often in close connection to the Archaelogy and Cultural Anthropology of the time.

One example is the Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (1858-1905) and his studies of stylistic development, which should be familiar to any student of art history. Many of Riegl’s observations are still foundational for how the history of ancient art in Egypt, Greece and the Roman empire is taught in basic courses in art history. Sometimes Riegl’s theories and historical schematizations have been described as a sort of ”proto-semiotics”. But how much validity is there in such claims? Following up on the earlier articles on Iconology, Meyer Schapiro and the Groupe µ, this was one of the questions posed in a speech given through video link from the Visual Studies ”home office” in Sweden for the Spring 2024 seminar series of GES (Grupo de Estudos Semióticos) at the public University of São Paulo (USP), 24 May 2024. We wish to thank our friend professor Elizabeth Harkot de la Taille for the kind invitation and the GES and FAPS (Fórum de Atualização em Pesquisas Semióticas) for the recording of the seminar, which is publicly available here:

The close and problematic relationship between Visual Semiotics and Art History (YouTube)

This post has been an overview of some of the activities in Visual Studies here in Åbo/Turku during 2019-2024, a difficult period in Academia and in the world at large. Much of this work has not taken place in Finland: the notion of the physical working place has started to evaporate here as in many other places of education and administration (at the same time as symbolical investments are made in lavish building projects, often resulting in spaces largely unused). Very often the teacher/coordinator of Visual Studies has only been present through Zoom or some other video connection from his home in Sweden. The topics of courses, articles and talks listed here may seem quite diverse and with little to connect them except a very general notion of ”Visual studies”. However, semiotics is a strong common factor that also has a bearing on more perceptual and psychological aspects, especially if one considers how Cognitive Semiotics connects the behavioural and social sciences to evolutionary theory, linguistics and cultural history.

The rabbit scribe, from the the Mayan drinking cup known as the ”Princeton Vase” in the archaelogical collections of Princeton University. Today’s Guatemala, Late Classic Maya (’Codex’ style), AD 670–750.

”The rabbit scribe”, taken from a 5th or 6th century drinking vessel of the Maya culture in today’s Guatemala, was used by Göran Sonesson as a visual signature in his letters and at his Lund University webpages. It signifies the importance of art history and anthropology for his research — he worked in Mexico as guest researcher in Ethno-linguistics during 1981-1983 and he has sometimes been referred to as both Linguist and Anthropologist. The rabbit also signifies the close connection between writing and pictures in the development of writing systems — Mayan script being a hieroglyphic script, like ancient Egyptian writing. The rabbit paints/writes the hieroglyphs on a piece of prepared animal skin that is placed on a flat writing board on the ground, but the way this writing arrangement has been rendered in the picture also makes it look quite exactly like a modern laptop seen from the side. Today, when historical fake news produce the most outrageous interpretations of details of ancient pictures, sometimes with the aid of visual AI, one should treat such associations with great care. But the possible laptop association was also for Sonesson a humourous reference to how past and present are connected in research that investigates the meaning of signs and symbols. A both Anthropological and Semiotic rule is that human beings tend to perceive meaning everywhere. Mayan script will probably never be completely deciphered and we cannot know exacly what the rabbit meant – but it was most probably not meant as a humorous detail only. The rabbit had an important role in Mayan mythology and scribes were venerated as people with a special connection to the gods.

The rabbit signature reappeared in a ”visual abstract” that accompanied Göran Sonesson’s last research article, published only three months before his untimeley death in March 2023. (See picture above.) An enormously productive author and researcher, Göran contributed decisively to the establishment of Semiotics as a recognized academic discipline in the Nordic countries. Together with such scholars as Thomas C. Daddesio, Per Aage Brandt, and the members of Groupe µ, he took part in transforming semiotics — earlier associated mostly with lingusitic models and methods — into the more open and diverse field that it is today. His contributions to this process will most certainly have a lasting significance. Göran didn’t cease working even during his last year of illness, and after his retirement in 2019 he was still strongly present in academic life and in the activities of semiotic associations. During those final years, he took part in the organization of several academic conferences and coordinated such initiatives as our Visio project.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the work of Göran and its continuation in courses and research projects on Cognitive Semiotics basically aims at clarifying how people think (the cognitive part of semiotics) and how all scientific thinking (also ”pure mathematics”) has an Anthropological aspect. This is not a question of subjective or ”humanistic” experience as opposed to ”objective scientific truth”, but of the relevance of methods and research questions for our self-knowledge and the future of our species. Jordan Zlatev has summarized this nicely in his notion of the conceptual-empirical loop: behavioural science creates hypotheses and models, but these should preferably be based on real experience, ”experience” then being defined as both subjective or introspective experience (first-person perspective, or the researcher’s own self-knowledge) and the observation of the behavour of others (second-person perspective). Philosophically speaking, this means that phenomenology as the very general description of ”what exists in the mind” should be the basis of all science (”science” in a wide sense) that deals with human life.

But often science only follows standard methods and standard protocols. The consequences of this are clearly to the seen in Society. Patients are being diagnosed routinely (and sometimes even without meeting the doctor) according to standard definitions of diagnostic manuals. Organizational reforms are carried out on the basis of general measures of efficiency and time management — but with very little regard of how work actually ”works”. The human mind is more and more seen as merely a machine for information processing and execution of algorithms, easily replaced with robots and generative AI. When academic teachers describe learning and the writing of student assigments as ”handling information” we can see how this thinking affects even those who should be at the forefront of critical opposition.