Distance education researcher Michael Barbour suggested during a recent webinar (19/5/2021) that pandemics have been and will be a recurring phenomenon. During the webinar on remote teaching in K-12 education that Umeå University hosted, Barbour encouraged education providers to prepare for a future with pandemics (not without). There is no going back to normal. Pandemics may become the new normal in (higher) education that forces us to stop, re-think and better our teaching and learning practices.

Distance education researcher Michael Barbour suggested during a recent webinar (19/5/2021) that pandemics have been and will be a recurring phenomenon. During the webinar on remote teaching in K-12 education that Umeå University hosted, Barbour encouraged education providers to prepare for a future with pandemics (not without). There is no going back to normal. Pandemics may become the new normal in (higher) education that forces us to stop, re-think and better our teaching and learning practices.

During the months with emergency distance education, new practices have emerged where the virtual spaces have become more interactive and collaborative in a sense. Students and teachers have become more at ease with these new forms of communication (chats, discussion forums, videoconferences) and different digital tools (online quizzes, breakout rooms, interactive whiteboards).

There are obvious benefits to recorded lectures and other digital materials that anyone can access at any time. With this follows issues of information overload when all courses are quickly moved online. What is the most important material for this course? What is essential to know after studying the material? How can teachers follow up on potential issues with the material and possible misunderstandings? Other questions are related to different types of materials and who can access them. Is the material accessible to all students? Who may be excluded from using the material? These are just some examples of how we can use this new normal to stop, re-think and better teaching practices in higher education.

The time spent together in the virtual spaces can become more focused and effective. Small-group discussions online can be rewarding although many teachers and students report a large drop-out rate when breakout rooms in Zoom are opened. This is something to consider from now on and raises a lot of interesting questions. When are discussions meaningful in relation to the content to be learned? Are they carefully planned parts of the course? In what ways are discussions followed up by the teachers afterward? How can discussions be re-designed so that more students actually participate in them? Are students in higher education not used to or comfortable with group discussions? Or would they walk out on discussions on-campus too if they could?

From a research point of view, it’s not surprising that many students avoid group discussions and group work in general. Many students don’t see the benefits of this method, for example, new and interesting perspectives on the content, better social relations, deeper knowledge, better social and communication skills. Supporting students in different ways to take part in them would be important when we move into another fall with the pandemic.

This year has taught us that many students are struggling alone and we need to re-think safety nets for all students. In large courses, more teachers could be one way to follow up on group work and support students who may be struggling to reach out. On-site meetings in small groups may be possible ways to support social interactions between students (and teachers), too. Better guidelines for group discussions and time for establishing social relations within the groups are other ways to re-design them.

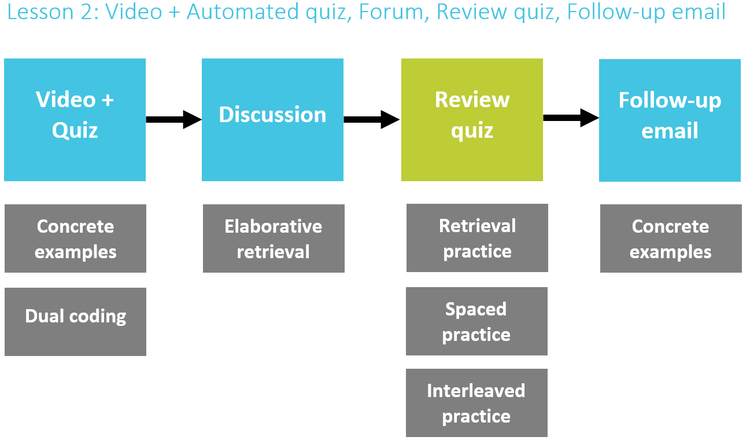

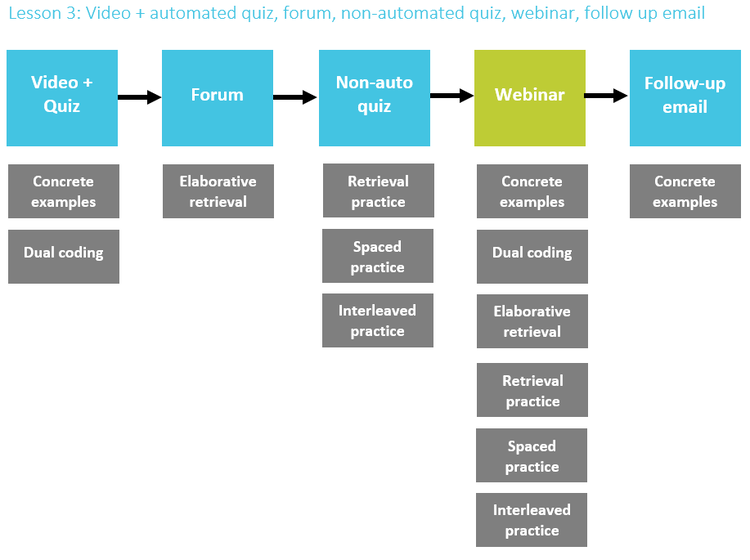

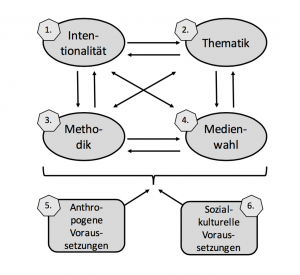

Anna Åkerfeldt and I wrote an article about re-designing distance courses when it comes to social and teaching presence in upper secondary schools and adult education (2020) that may be useful in higher education. For example the importance of considering content, methods and digital tools used:

The upper secondary school teachers adapted methods of collaboration (mind maps, quizzes, synchronous and asynchronous discussions). Further, the assignments were redesigned to increase student collaboration, for example, by maintaining the same groups during the course to intellectually focus the group work early on and allow for relationships building over a more extended period.

If this really is the new normal there are other pressing issues to consider relating to the digital platforms we use (Teams, Yammer, Zoom). In their editorial Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency Ben Williamson, Rebecca Eynon and John Potter (2020) write:

Many of the world’s largest and most successful technology businesses have also expanded their educational services rapidly, including Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Zoom. Markets have long been a central concern of the global edtech industry, but the pandemic may have presented it with remarkable business opportunities for profit-making, as well as enhanced influence over the practices of education.

If higher education will become even more platform-based in the future (as some researchers suggest), educational institutions, national governments and international stakeholders need to be (even more) critical of the platform providers, their access to data produced by personnel and students, and their impact on teaching and learning practices. Jarke and Breiter call this the The datafication of education (2019):

the education sector is one of the most noticeable domains affected by datafication, because it transforms not only the ways in which teaching and learning are organised’ and raises expectations about ‘increased transparency, accountability, service orientation and civic participation but also associated fears with respect to surveillance and control, privacy issues, power relations, and (new) inequalities’

Creating and maintaining safe, inclusive, meaningful and creative virtual spaces for teaching and learning is important. We may ask if the virtual spaces we are using at the moment help or hinder us from teaching and learning? What could these kinds of safe, inclusive, meaningful and creative spaces look like, what functions would they need to include, if we, for example, want to support collaboration among students and personnel better in the future?