WRITTEN BY Fatema Zohra, MASTER’S STUDENT, ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY

When I began the course The Geography of Social Exclusion, I had little understanding of social imaginary borders and their impact on our social lives. Learning how COVID-19 and social imaginary borders intersected was fascinating, creating invisible divisions among countries during the pandemic. However, this made me reflect on the concept of borders within Dalit society. In my theology course, I studied Dalit Liberation by Rajkumar Panin, which deepened my understanding of caste-based exclusion. in this blog, I will briefly share my thoughts and realizations on how social imaginary borders apply to the Dalit people.

Social imaginary borders establish symbolic and institutional boundaries that people employ to create separations between each other while enforcing social exclusion. Dalits remain separated from others by social borders that combine caste prejudice with religious control systems and political status regulations that establish their societal position (Shah, 2020).

Rajkumar shows that the Indian Church has maintained caste divisions as part of its historical traditions even though it exists as a sacred spiritual institution. Dalits face marginalization in Christian communities because the Church fails to develop radical ethical principles that combat caste-based oppression. It shows that social barriers promoting discrimination exist even inside organizations that claim to champion equality and disorder (Peniel, 2010).

For many centuries Indian social discrimination known as “untouchable” has targeted the Dalit population as a result of India’s rigid caste system. The extensive presence of caste-based discrimination within India’s social, economic political, and religious structures keeps Dalits from taking full part in society. The Dalit theological movement successfully focuses on liberation yet insufficiently breaks down the core systems that enable discrimination according to Rajkumar (Peniel, 2010).

Caste-Base Discrimination against Dalit

1. Socio-cultural Exclusion

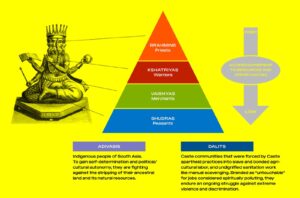

Traditional Indian social and religious organizations maintain the exclusion of Dalits because they perceive Dalits as impure. Through Hindu ideology, the caste system persists as a social system that divides people using four main categories called varnas (Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra) and places Dalits outside these groups. Through caste classification society created “untouchability” as a practice that denies participation to Dalits:

- Individuals who belong to the lower caste must avoid accessing religious sites and places dedicated to worship.

- The practice of sharing food or water sources remains forbidden for lower-caste individuals when it involves persons from higher-caste backgrounds.

- Religious ceremonies alongside festive events form part of their participation every year.

- People from all castes reside within the same residential communities.

Due to these restrictions, these individuals maintain their position as social outcasts which prevents them from effectively integrating with the mainstream population (Shah, 2020; Peniel, 2010).

2. Economic Exclusion and Forced Labor

Historical oppression has restricted Dalits from performing tasks such as sewage cleaning, animal disposal, and manual scavenging work because of their discriminatory position. Dalits remain segregated into substandard work despite the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act (2013) because caste prejudices run deep in Indian society.

Economic exclusion also manifests in:

- A denial of land ownership prevents many Dalits from accessing farmland resulting in their dependent labor positions.

- Professional discrimination against Dalit applicants by higher-caste employers triggers unemployment, poverty, and employment segregation.

- Dalits receive wages much lower than those paid to upper-caste workers while doing equivalent work.

3. Educational Exclusion and Discrimination in Schools

Dalit students face discrimination within the Indian education system because it restricts their possibilities to access high-quality schooling. Students from Dalit backgrounds face two school-based discrimination practices in certain rural locations where teachers segregate them from other pupils through separate classroom seating arrangements and they also limit their school meal consumption rights. Dalit student dropout rates rise because of bullying combined with caste insults and insufficient academic support which forces students to leave school prematurely. Many Dalits face barriers to accessing quality universities because they face obstacles which include high costs of education as well as discrimination even though affirmative action policies offer some opportunities (Shah, 2020).

How This Social Exclusion Happens: The Structural Reinforcement of Caste

The system of caste discrimination exists through four interconnected elements that include social learning processes alongside theological arguments, legal failures, and political disregard. Religion supports the maintenance of the caste system through scripture regulations which describe a heavenly social ranking. Religious organizations preserve caste differences despite making official changes to their practices. Children learn discrimination through generations by receiving it as an allegedly natural part of social customs. The systems of protection meant for Dalits suffer from inadequate law enforcement which enables discrimination against them to continue. Many Dalits stay dependent on upper-caste landowners and employers which creates barriers for them to fight against oppressive working conditions (Shah, 2020; Peniel, 2010).

The caste-based discrimination that exists at every point in life blocks Dalits from accessing the social community. Rajkumar finds faults with Dalit theology because it concentrates on theoretical liberation concepts instead of targeting concrete social inequalities. Dalits can only achieve their social equality when the caste hierarchy receives dismantling through simultaneous legal as well as social and religious reforms that empower them to restore their proper social standing (Peniel, 2010 ).

References:

Shah, G. (2020). Social exclusion, caste, and health: A review based on the social determinants framework. Contemporary Voice of Dalit, 12(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023020963317

Peniel, R. (2010). Dalit theology and Dalit liberation: Problems, paradigms, and possibilities. Routledge.