Written by Sandis Sitton

Borders are a complicated concept. What they are, how they look, are enforced, or what they have been called has changed throughout history1. Research has shown that even the conventional concepts of national borders resulted from very specific evolutions in notions of territoriality and the relationships between power, land, and people2. Today they are geographical and institutional together, inclusionary in one sense while necessarily exclusionary as a cost, and how changes depending on where these lines are drawn, how, and for whom.

Enter Puerto Rico, U.S. Territory

Under the control of the United States, Puerto Rico has been the center of several controversies involving the rights and powers of the locals there over Puerto Rico itself. These range from the decades-long military occupation of its islands, their exploitation and pollution, and the forced relocation of their inhabitants3, to the mitigation of its local government’s power to self-govern and direct seizure of its control over its own financial policies 4. All of this has happened under the facilitation of the very law of the land, the institutions and policies which define Puerto Rico as a place. Instrumental to this, of course, is the border.

What Kind of Border Does Puerto Rico Have?

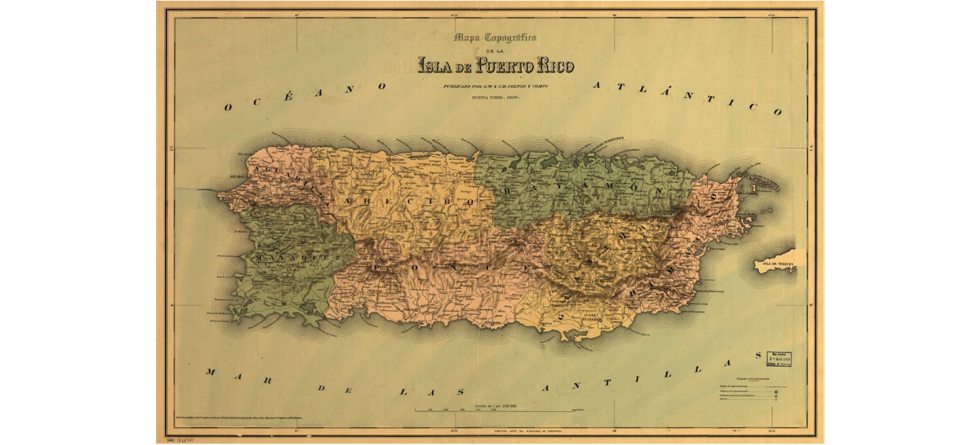

The archipelago was first a colony under Spain following Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492. They traded hands into the possession of the United States in 1898 due to the Spanish American War, at which time ownership of the land and the national status of its people was changed, and the border around it and its meaning changed with it.

Today Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory, one of five the United States owns, including the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Marianas Islands, although it does have other territories without permanent populations and relationships with the Free Associated States which it does not directly govern5. However, Puerto Rico and the other unincorporated territories are still governed by the United States federal government above their own. Though like the Northern Marianas Islands, Puerto Rico is also considered a Commonwealth, with its own constitution and elected local governments, the Puerto Rican government must still uphold the U.S Constitution as well as its own6.

This relationship originates back to the Jones Act of 1917, the first written legislation to define Puerto Rico’s involvement with the United States7. Under the act, Puerto Rico was defined as unincorporated, meaning not a part of the United States or, consequently, not represented in the U.S. Constitution8. This was allowed based on the reasoning in a 1900 Supreme Court case titled Downes v Bidwell, where the court determined that some territories could be incompatible with the U.S. Constitution, saying this:

“[For] possessions inhabited by alien races differing from [the people of United States] in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought, the administration of government and justice according to Anglo-Saxon principles may for a time be impossible.”9

As such, the role and rights of citizens in Puerto Rico and why they are different from those in the states themselves are directly connected to the perception of difference, legally tied to the land of the territory itself.

What does this make Puerto Ricans?

Residents of Puerto Rico are still U.S. citizens and do have access to the other states, even to move there and integrate as any other citizens could. 5.83 million Puerto Ricans were estimated to live in the United States proper (the 50 states themselves), steadily rising10. Puerto Ricans living in the states have all the rights of other citizens; they can vote for federal representatives in the federal government, including the President, Senators, and members of the House of Representatives11. In this respect, Puerto Ricans are not excluded from the rights established in the Constitution because there are institutional obstacles that obstruct them from its guarantees12.

Locals still pay federal taxes like people of any of the states, though some do not need to pay income tax, and they are still subject to all federal laws and obligations, like military service in the form of the draft13. They still serve voluntarily in the military, like any other citizen of the United States, however, despite these similarities, they cannot vote in federal elections and have no voting representatives in Congress for long as they remain residents in Puerto Rico13. They bear the duties of full citizenship, but their membership is contingent on their place within its borders.

Puerto Ricans, then, are not Americans, not in all of the ways that matter. Because the land they live on is governed by different rules than the States, so are the people themselves. They may inhabit the islands, but they do not share equally in their ownership, their governance, or in the rewards to the society that does.

References:

1 Brunet‐Jailly, E., 2009. The State of Borders and Borderlands Studies 2009: A Historical View and a View from the Journal of Borderlands Studies. Eurasia Border Review Part I < Current Trends in Border Analysis >.

2 Ibid.

3 Lawrence Wittner, “Breaking the Grip of Militarism: The Story of Vieques,” History News Network, February 28, 2019, https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/171839.

4 Nick Brown, “Puerto Rico Authorizes Debt Payment Suspension; Obama Signs Rescue Bill,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, June 30, 2016), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-puertorico-debt-idUSKCN0ZG09Y.

5 Francisco H. Vázquez, Latino/a Thought Culture, Politics, and Society (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009), 374-375.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Henry Billings Brown and Supreme Court Of The United States. U.S. Reports: Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244. 1900. Periodical. https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep182244/, 287.

10 U.S. Census Bureau , “B03001 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN,” United States Census Bureau (United States Census Bureau, 2019), https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B03001%3A+HISPANIC+OR+LATINO+ORIGIN+BY+SPECIFIC+ORIGIN&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B03001&hidePreview=true.

11 Tom C.W. Lin, “Americans, Almost and Forgotten,” California Law Review 107, no. 4 (August 2019), https://doi.org/https://www.californialawreview.org/print/americans- almost-and- forgotten/#:~:text=There%20are%20millions %20of %20Americans,and %20die%20defending%20our%20Constitution.

12 Andrew M. Fischer, “Reconceiving Social Exclusion,” BWPI Working Paper, no. 146 (April 2011), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1805685, 17.

13 Tom C.W. Lin, 2019.

14 Ibid.