Written by Sandis Sitton

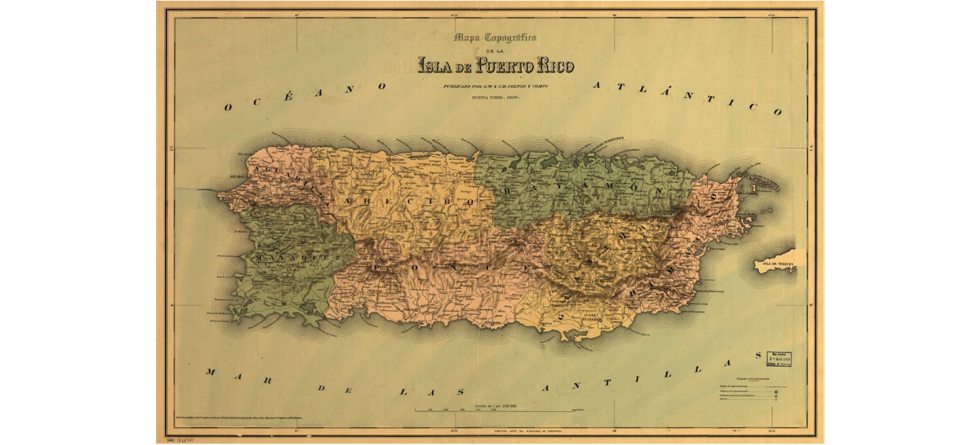

In my last blog, I discussed how the border of Puerto Rico can be understood as an institutional tool that transfers various kinds of power over the lands of the territory to those in the mainland United States and how inclusion in the United States under those conditions means exclusion for local Puerto Ricans from other institutions of power which other states are guaranteed under the Constitution. This time, I’d like to look at how migration off the islands and into the United States is motivated not just by local conditions but also by exclusionary policies like those already explored, which obstruct locals from political power and their local markets and economic policy as well.

Is Puerto Rico a Fragile State?

One reason migrants will often travel to a country is to improve on their material conditions, find work, and/or transition out of areas of hardship or shortage1. This is undoubtedly a component of Puerto Ricans’ reasons for migrating to the mainland states. The islands in 2017 suffered immense devastation at the hands of two subsequent hurricanes, leading to lives lost in the thousands and catastrophic infrastructural damage, conditions which were directly credited for the emigration of over 200,000 locals to the mainland states2. These situations certainly contribute to the fragility of the state, a known motivator for emigration to places of greater stability3.

States can be called fragile for several reasons. They can lack the full capacity to govern their populations and territory or cannot provide security and economic opportunity4. However, the economic, environmental, and political conditions in Puerto Rico prompt migration to the mainland states do not extend to everyone involved. For some, the fragility of Puerto Rico is not a reason for emigration, but immigration, as attempts to rebuild it, has instead created a new opportunity. In this space where there is an opportunity for some but continued fragility for others, we find new processes of exclusion unfolding in the territory.

Fragility for Some, Opportunities for Others

While conditions for the locals have indeed been difficult, especially in comparison to the rest of the U.S., that is not to say there are no opportunities there at all, only that there are none for them. The main island of Puerto Rico has, in recent years, seen massive growth in its housing market. Thousands of mainland Americans have moved or applied to move their place of residence to the commonwealth because of policies made by the local government to attract outside investment5. For example, policies like Act 60 create tax breaks for people moving to the island as a way to revitalize the local housing market. Still, the tax breaks offered to newcomers are unavailable to those who already live there6. This has been something of a success; in 2021, house sales rose 84% from the previous years7. At the same time, however, new housing construction has remained stagnant or even fallen8. Because of this, locals, 43% of whom live under the federal poverty level are being priced out of neighborhoods they could once afford to live in. Many have had to leave the island entirely, searching for work and affordable housing, while new investors buy and repurpose properties as vacation housing9. Some decry the often-wealthy newcomers as colonizers and say their country is being sold out from under them10.

Not Poverty, but Exclusion from Opportunity

These circumstances create a situation of exclusion for locals, whose towns are being invested in, while they are kept apart from the benefits of that growth. Exclusion often comes in situations wherein there are obstacles to upward mobility, which are not always direct or evident because their effects are only seen in overlapping structures and institutions11.

For this reason, it is not always solely an issue of poverty, or any such condition, even in cases where they do create significant problems12. Puerto Ricans who endured several natural disasters in succession, under an economy and government that were heavily restricted under restructuring plans, often had to pay for the reconstruction of their neighborhoods with their labor13. Sometimes they waited years, if not still to this day, for the government to step in and take on this burden for them14. Now, though, the territory is shifting to accommodate new markets, prices change, and the cost of living with it. Puerto Ricans are not only poor but excluded from the same policies that attract people to these markets; they are experiencing states of fragility that others are not.

References:

1 Anke Hoeffler, “Out of the Frying Pan into the Fire? Migration from Fragile States to Fragile States,” OECD Development Co-Operation Working Papers, (2013), https://doi.org/10.1787/5k49dffmjpmv-en, 4.

2 Nicole Acevedo, “Puerto Rico Sees More Pain and Little Progress Three Years after Hurricane Maria,” NBCNews.com (NBCUniversal News Group, September 20, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/puerto-rico-sees-more-pain-little-progress-three- years-after-n1240513.

3 Anke Hoeffler, (2013), 6.

4 Ibid.

5 Coral Murphy Marcos, Patricia Mazzei, and Erika P. Rodriguez, “The Rush for a Slice of Paradise in Puerto Rico,” The New York Times (The New York Times, January 31, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/31/us/puerto-rico-gentrification.html.

6 Ibid.

7 Lelaine C Delmendo, “Puerto Rico’s Housing Market Gaining Momentum,” Global Property Guide (Global Property Guide, October 16, 2021), https://www.globalpropertyguide.com/Caribbean/Puerto-Rico/Price-History.

8 Ibid.

9 Coral Murphy Marcos et al., (2022).

10 Ibid.

11 Andrew M. Fischer, “Reconceiving Social Exclusion,” BWPI Working Paper, no. 146 (April 2011), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1805685, 23.

12 Ibid.

13 Nicole Acevedo, (2020).

14 Ibid.

This massive amount of debt serves as an enormous claim on the future wages of the working class, and it also works to make sure that they have the most challenging time earning enough even to begin paying it off.

This massive amount of debt serves as an enormous claim on the future wages of the working class, and it also works to make sure that they have the most challenging time earning enough even to begin paying it off.