An EU official hangs the Union Jack next to the European Union flag at the VIP entrance at the European Commission headquarters in Brussels on Tuesday, Feb. 16, 2016. British Prime Minister David Cameron is visiting EU leaders two days ahead of a crucial EU summit. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

”Historikerbloggen” publish a contribution on Brexit, authored by Norry LaPorte, historian and Reader in Modern European History at the University of South Wales. In the blog, LaPorte gives us his own view and interpretation on the context and the consequences Brexit will have on Great Britain once the result of the referendum became evident on the morning of Friday 24 June. LaPorte’s research focus primarily on Europe’s radical history during the twentieth century, and he has published numerous articles and books on this topic, e.g. on the German Communist Party and one of its leading figures Ernst Thälmann; the Communist International and the implications of Bolshevization and Stalinization on the international communist movement between the wars.

”Historikerbloggen” publicerar ett bidrag om Brexit författad av Norry LaPorte, historiker verksam vid University of South Wales. I bloggen ger LaPorte sin syn på Brexit och dess konsekvenser för Storbritannien efter att resultatet av omröstningen stod klart på morgonen fredagen den 24 juni. LaPortes forskning fokuserar primärt på Europas radikala historia under 1900-talet, och han har publicerat artiklar och böcker om det tyska kommunistpartiet och en av dess ledargestalter Ernst Thälmann; den Kommunistiska internationalen och hur ”världspartiet” påverkades av bolsjevisering och stalinisering under mellankrigstiden.

Norry LaPorte,

Reader in Modern European History at the University of South Wales,

6 July 2016 (with thanks to Jane Finucane)

In the aftermath of the vote to leave the European Union, a widely viewed satirical video appeared on Youtube. A scene in the German film ‘Downfall’ carried spoof subtitles in which Hitler lambasted the Nazi leaders around him in the bunker: ‘You were not supposed to actually win’! To those who had vehemently opposed Brexit, there seemed to be more than a grain of truth in this. Before Michael Gove and Boris Johnson acrimoniously parted company – in the words of Scottish Nationalist Party leader at Westminster, Alex Salmond – they looked like they wanted to cry at their ‘victory’ press conference. At least Johnson seemed to realise why this would be a pyrrhic victory. As mayor of London, he knew that the City and its financial services risked sinking beneath the waves if it stayed on board Gove’s good ship Britannia, together with close to 50 percent of British exports.

For all its complexity, the campaign leading up to the ‘Leave’ vote in the referendum of 23 June was reduced to two messages: immigration (bad) and the economy (bad if we leave). So why did ‘Leave’ win as it risked making voters poorer? And why did ‘Remain’ lose when referenda usually opt for the least risky option, not least economically – as happened in the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence? One reason is that the ‘Remain’ campaign failed even to engage with the wider European project as a means to bring peace and prosperity to post-1945 Europe. Their only clear and consistent message was that you’ll have to pay the cost of leaving EU.

What caught the voters’ imagination – and secured their support – was a cross-class alliance held together by what we can term ‘project Britannia’: a denial of post-imperial decline after 1945, which has been tied to a very Conservative political project. A political discourse already so infused by references to the Second World War went into overdrive. In its referendum special issue the neo-conservative monthly Standpoint called the campaign the ‘Battle for Brexit’ in which ‘we’ were again standing up to the threat from Europe and the EU’s failed project of preventing ‘German domination’.

For 52% of the electorate, the message was seductive. Usual political alliances were thrown in the air as those traditional Labour voters living in post-industrial parts of England and Wales who have suffered from the impact of Chancellor George Osborne’s austerity policies stood on the same side of the debate as more affluent core Conservative voters in rural England. Both groups appear to have believed that ‘immigrants’ were the problem, even if there was not a foreign accent to hear for miles in most of the countryside. A discourse of xenophobia was spewed out by the tabloid press, which hammered out the ‘Leave’ campaign’s simplistic message: ‘take back control’. After decades of hostility to the EU, this large and influential section of the media called for ending the influx of migrant workers (who in reality have contributed significantly to the economy) and ending the so-called Diktat imposed from Brussels – it is only Europe, if you subscribe to this worldview, that does dictatorship, not the ‘mother of democracy’.

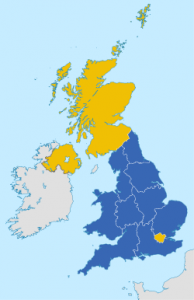

Yet, it became clear that the Brexiteers really did not have any plan for a future outside the EU, and social divisions and political discord defined post-referendum Britain. Prime Minister David Cameron resigned and the Tory government became a caretaker government. The opposition Labour Party fell into a civil war between the parliamentary party and the left-wing, Jeremy Corbyn supporting membership. The 48% who voted ‘Remain’ felt totally disenfranchised. The Brexiteers were dividing into ‘fundamentalist’ (no compromise on immigration) and ‘realist’ (a compromise on immigration to secure access to the EU’s single market) camps. In Scotland, the governing SNP reopened issues of Scottish independence as this part of multinational Britain voted 62% to 38% for ‘Remain’. Northern Ireland too voted ‘Remain’, which now risks all the achievement of the peace process encapsulated in the ‘Good Friday Agreement (1998). Will there really be a hard border dividing Ireland and risking a return to the troubles? According to the hard-line Gove, Westminster should never have appeased ‘Irish nationalism’ in the first place – after all, in his view, if you yield to one ‘demand’ what comes next?

So what did the potent slogan ‘take back control’ mean? Here there is something uniting two of the main candidates in the Tory leadership contest, Gove and Theresa May, beyond the focus on immigrant on ‘borders’ in a globalised world, which has led to a surge in hate crime as recorded by the police. They are enthused by the prospect of repealing the ‘Human Rights Act’ and the intervention of ‘foreign’ judges in the ‘European Court of Rights’ and European labour and working legislation has also been deemed unwelcome in deregulated, free-market Britain.

Is there a way back to the ‘imagined community’ trumped in the tabloid press and the Daily Telegraph when Britain ruled the waves, could stand alone and trade with the wider world? No. All great powers rise and fall, and this vote will only accelerate decline – from multinational state into a ‘Little England’ with Scotland, and perhaps even a re-united Ireland, returning to their common European home.

What, if anything, is the lesson from history in these uncharted waters? One point is to beware myths of national renewal which are exploited by right-wing populists and more readily believed by sections of society in troubled times. 1940 is not 2016 and fixating on Hitler’s ‘Downfall’ not only tells us about British humour but also about how nationalist myths defined against foreign ‘others’ and past battles obscure a positive vision of the future and ‘our’ place in it. The empire is gone and the war long over. Can’t we adopt another myth of Britishness: being a fair, open and hospitable people? It would be much better than Tory leadership hopefuls debating whether Europeans can remain in the UK.