By: Martins Kwazema, Doctoral Candidate in General History

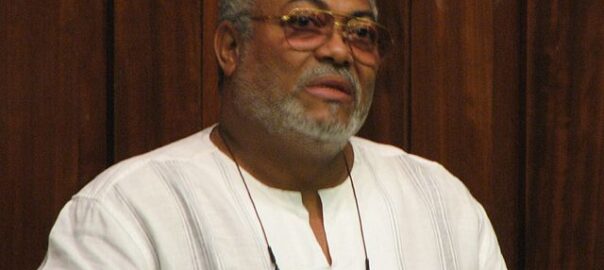

Although Jerry Rawlings’ leadership as president of Ghana spanned from 1981–2001, he was the leader of Ghana’s people’s revolution during the period 1982 to 1992. Under his leadership, Ghana was elevated to the status of an economic “success story” by the World Bank,[1] and recognized as a developing country with one of the most stable democracies in West Africa. On a personal level, Rawlings seemed to believe that he bore the responsibility of liberating the common man in Ghana from the clutches of exploitation, imperialism and foreign domination. He was adamant in pursuing his objectives amidst the difficult economic challenges that previous presidential regimes had created in Ghana through corruption in governance.

Moreover, he was resilient amidst forces that tried to extinguish his future visions for Ghana. Although he failed in his first attempt to seize power in the military coup of 15th May 1979, he was relentless in his pursuit to eradicate corruption in Ghana. He is popularly known for his phrase “Leave my men alone”[2] which he proclaimed while defending his men in the dock of the military tribunal where he was indicted after the failed coup. He was also a populist and often bought the hearts of the people through his oratory and mannerisms with which he identified with the struggles of the common man. One of such instances was when he gave a foundational reason behind his attempt at the failed coup in these words:

I am not an expert in Economics and I am not an expert in Law, but I am an expert in working on an empty stomach while wondering when and where the next meal will come from, I know what it feels like going to bed with a headache, for want of food in the stomach.[3]

Due to his defense for his men during his trial in the docks of the military tribunal and his willingness to bear all the responsibility and punitive actions against the perpetuators of the May 15th coup d’état, other soldiers believed he could represent a source of protection to them as well as a mouthpiece for their struggle against the elite. As a result, the soldiers of the lower ranks in the Army developed trust in his vision and conspired to break him out from prison on June 4th, 1979. After his jail break, he went on to lead one of the bloodiest political and economic revolutions in West Africa popularly known as the June 4th and December 31st revolutions.

The June 4th revolution was a military coup that was initiated by Rawlings and his AFRC (Armed Forces Revolutionary Council) government due to the heightened level of economic decadence that Ghana had sunk in since its independence. The central objective of Rawlings’ AFRC government was a “house cleaning”.[4] The house cleaning in question encompassed the destruction of corruption, and the socioeconomic and political structures that constantly proliferated the economic exploitation of the people of Ghana. With mounting pressures against the military regime in Ghana, Rawlings relinquished power to Hilla Limann’s civilian government.

No sooner had Limann governed for two years, than Rawlings led another military coup that seized power from the civilian regime of Limann. Rawlings argued that Limann’s regime was incapable of curbing the thieves, rogues and structures that constantly exploited the people of Ghana. He argued the Limann’s regime simply deepened the already worrisome economic decadence that Ghana was faced with at the time. Hence, on December 31st 1981, Rawlings struck once more at governance, seizing power and igniting a people’s revolution that aimed at giving power to the common man by involving the ordinary Ghanaian in decision-making. This revolution is popularly referred to as the December 31st revolution.

In my doctoral research, I am investigating the December 31st revolution using the past futures framework (PFF).[5] One central objective of my doctoral project is to develop a conceptual framework for investigating history and applying it to understand the Ghana’s people’s revolution. The timeframe I have chosen is 1982–1992. In definitive terms, the PFF is a futures literacy tool developed to aid understanding of the complexity of the present. The framework advocates that historical investigation of the past should consider the trajectories by which anticipations in the present transform into past-futures in the past. Such a mode of investigating the past then divulges the possibilities for forward and backward movements in our attempt to understand the past and write history. I have fleshed out the theoretical concepts behind the framework here.

Based on the past futures framework analysis of the December 31st people’s revolution in Ghana, the period spanning 1982 to April 1983 is designated as the first past-future of the revolution. This past-future is rhetorically and ideologically characteristic of an anti-imperialist, anti-neocolonialist populism.[6] However, the period spanning April 1983 to 1992 is designated as the second past-future of the revolution. This phase of the revolution is heavily characteristic of a neoliberal populist rhetoric driven by a fiscal ideology.[7] The fiscal ideology in question was undergirded by the infusion of the IMF and World Bank SAP (Structural Adjustment Programme) aid into the economic recovery plans for Ghana in the 1980s and 1990s.

The victors of the December 31st revolution might have stepped on many toes in Ghana at a personal level, but it is no doubt a period in Ghana’s sociopolitical and economic history when Ghana’s historic economic downturn experienced a slight upturn. One interesting finding of my project is the fact that the economic upturn, the tune to which the World Bank proclaimed Ghana to be one of its success stories at the time, required a transmogrification of Rawlings’ PNDC (Provisional National Defence Council) government into a dictatorial counter-revolutionary regime. The transmogrified character of Rawlings’ PNDC government during the revolution’s second past-future was in contradistinction to the original objectives that propelled the December 31st revolution.

Hence, it is indeed striking that the economic policies and development plans sponsored and heavily influenced by Bretton Woods institutions like the IMF and the World Bank would thrive under a militaristic, dictatorial regime. One would think that Democracy should be the utmost political vehicle through which such economic policies thrive. In conclusion, what this dichotomy forces me to reflect on at a wider personal level is the question of whether Democracy is supported or advocated for by the definition and measurement of “success” as determined by such fiscal institutions. It is common place that the world condemns coup d’états and military dictatorships such as have recently occurred in Mali (May 2021) and Guinea (September 2021). However, I am poised to ponder on whether the world would condemn these regimes if the nations they govern are proclaimed “successful” in driving economic reforms sponsored by these fiscal institutions for the benefit/detriment of their citizens after a few years in power. We could also ask, whose definition of “success” is most appreciable here… the fiscal institutions or the people? I am still thinking!

[1] Darko Kwabena Opoku, ‘From a ‘success’ story to a highly indebted poor country: Ghana and neoliberal reforms’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies 28, no.4 (2010): 155.

[2] Jesse Weaver Shipley (2020). The passing of Jerry Rawlings, https://africasacountry.com/2020/11/the-passing-of-jerry-john-rawlings. Accessed 6th October, 2021.

[3] Acquah, K. K. (2002). A Letter to Kantinka: A Synopsis of Socio-politico-economic Situation in Contemporary Ghana. Kanda-Accra: Dynamo Publishers.

[4] Paul Nugent, “Nkrumah and Rawlings: Political Lives in Parallel?”, Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, New Series, no. 12 (2009):

[5] Kwazema, M. (2021). The problem of the present in West Africa: Introducing a conceptual framework. Futures, 132. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102815

[6] Kodwo Thompson, “Revolution and the Devalued Cedi,” Daily Graphic, October 11, 1982, 3.

[7] Baffour Agyeman-Duah, Ghana, 1982-6: The Politics of the P.N.D.C, The Journal of Modern African Studies 25, 4 (Dec., 1987)

Martins Kwazema, Doctoral Candidate in General History. His doctoral project investigates the "past futures" of the December 31st Revolution in Ghana during the period 1982-1992.